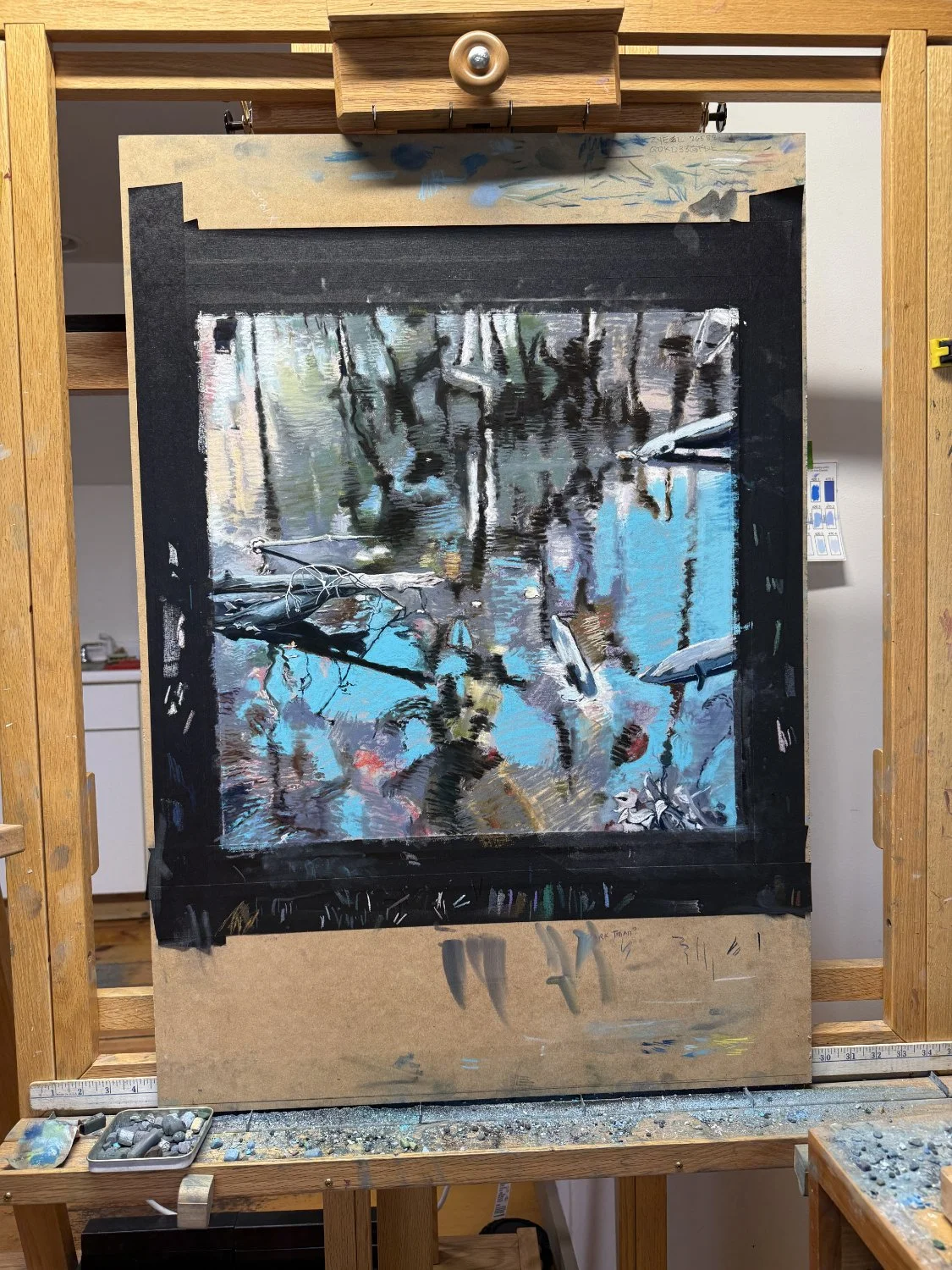

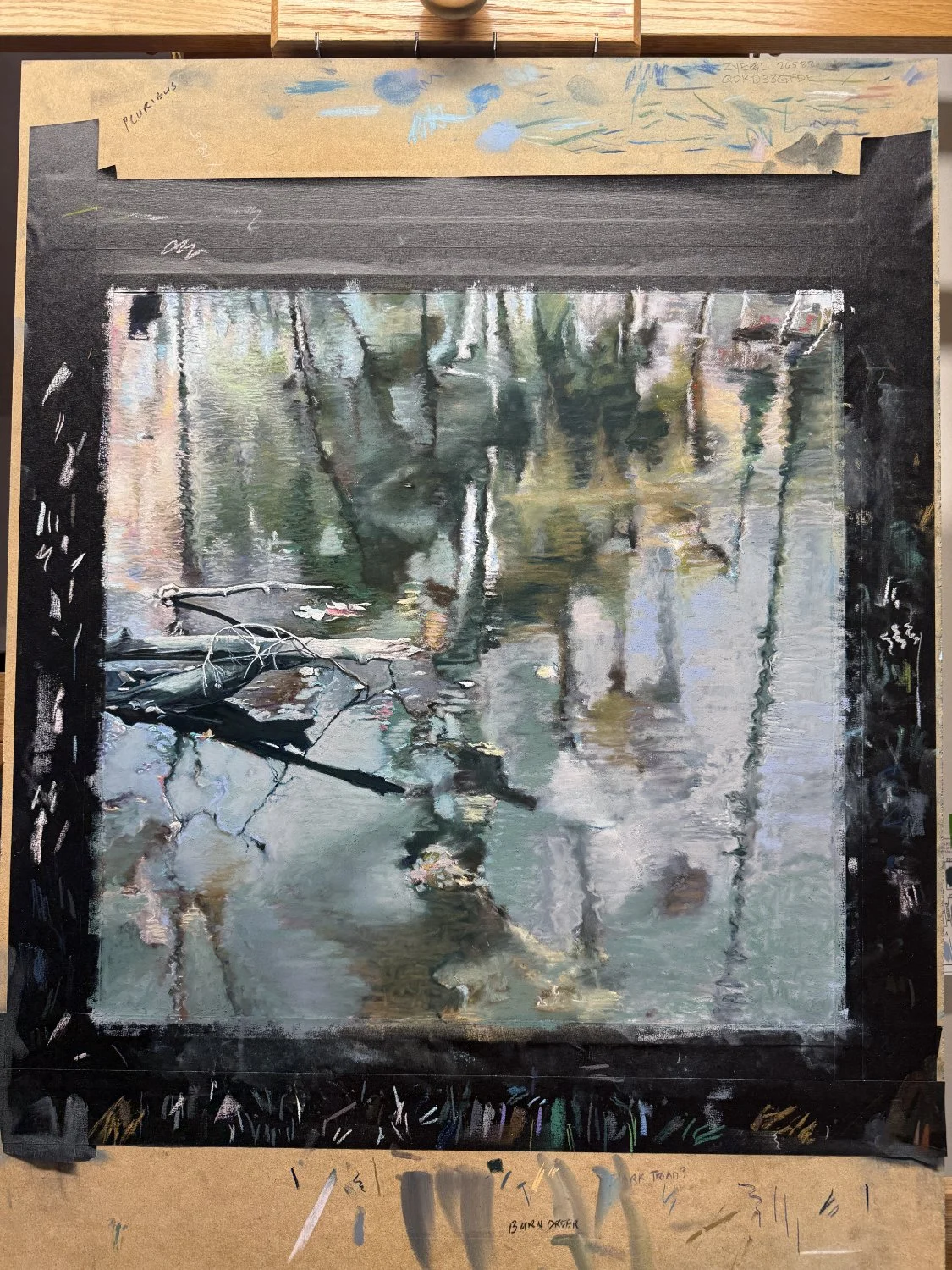

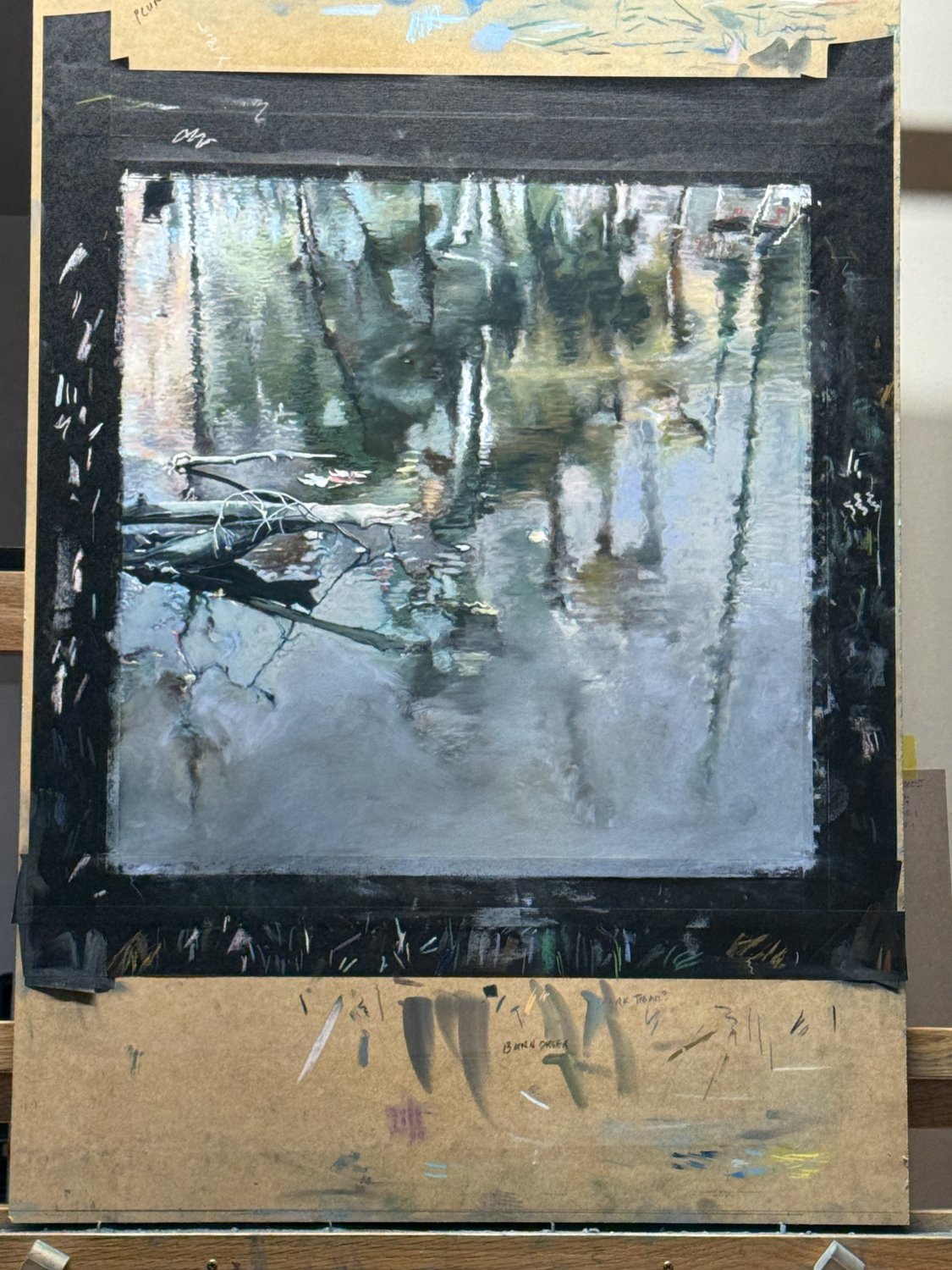

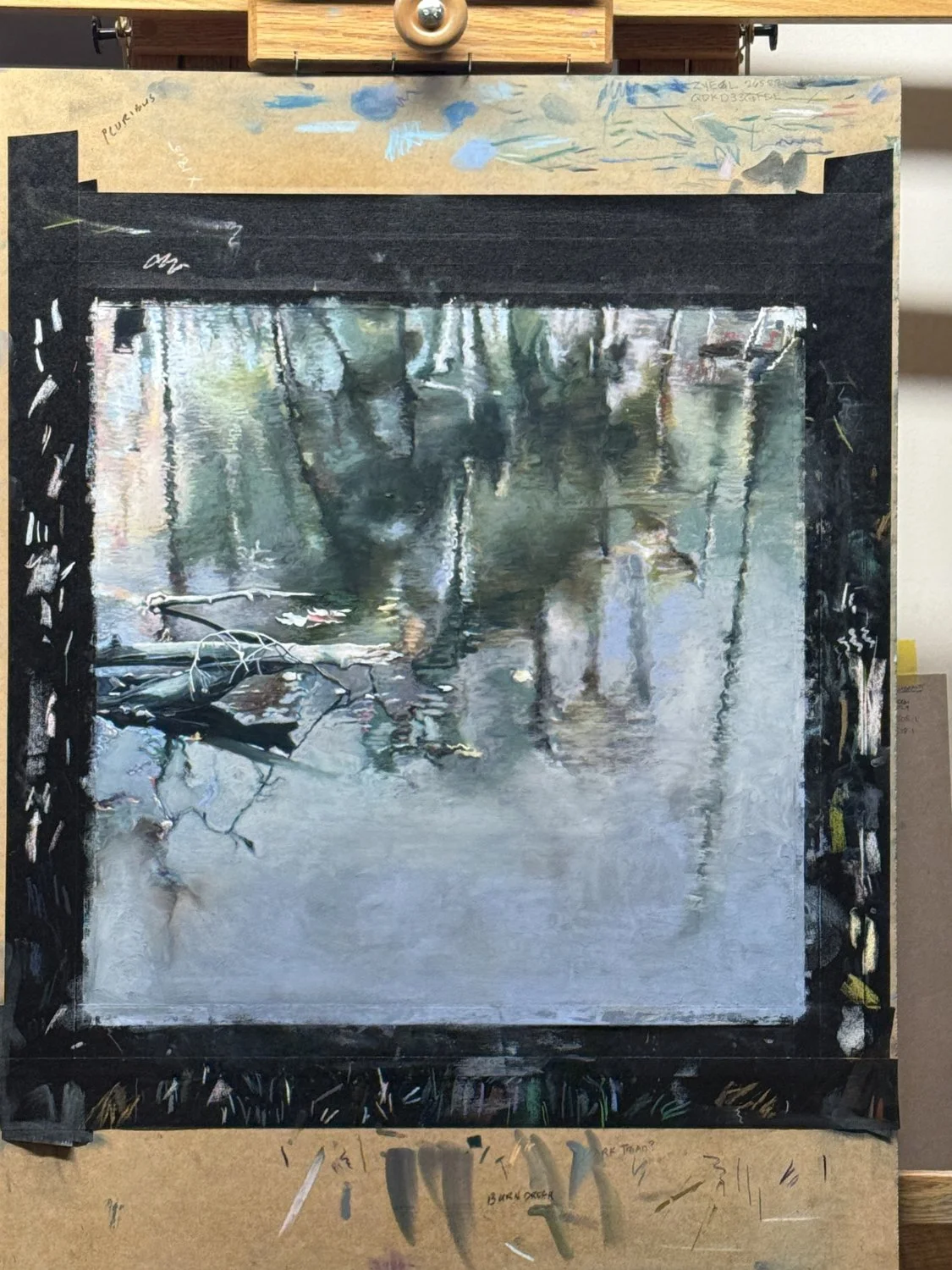

Evolution of a painting

I thought you, whoever you are, might like to “see under the hood” — this is how my most recent painting evolved from a reference photograph to a finished piece. As you can see, it was quite a struggle for me. I have been working to find a balance between representational painting and more formalist concerns (composition, rhythm, value, color, and light). I am particularly interested in the liminal space between representation and abstraction.

Throughout this process, I knew I had to simplify my image and concentrate on how the elements were working relative to eachother and the square paper. In the beginning, there were simply too many elements. Additionally, the saturated turquoise of the water was in competition with my focal point: the rotten log. I had to throw a lot away and to move slowly enough to recognize the lovely accidents that occurred as I edited. I was originally intrigued by the rhythmic progression of verticals with the strong horizontal of the log in this photograph, and I focused on that as I worked through this painting. I am also very interested in the marks I make with pastels. I don’t smear or blend my pastels with my fingers or a tool. Any blending that occurs happens when I overlay one color on another. As a result there are many lines in the painting that I like very much.

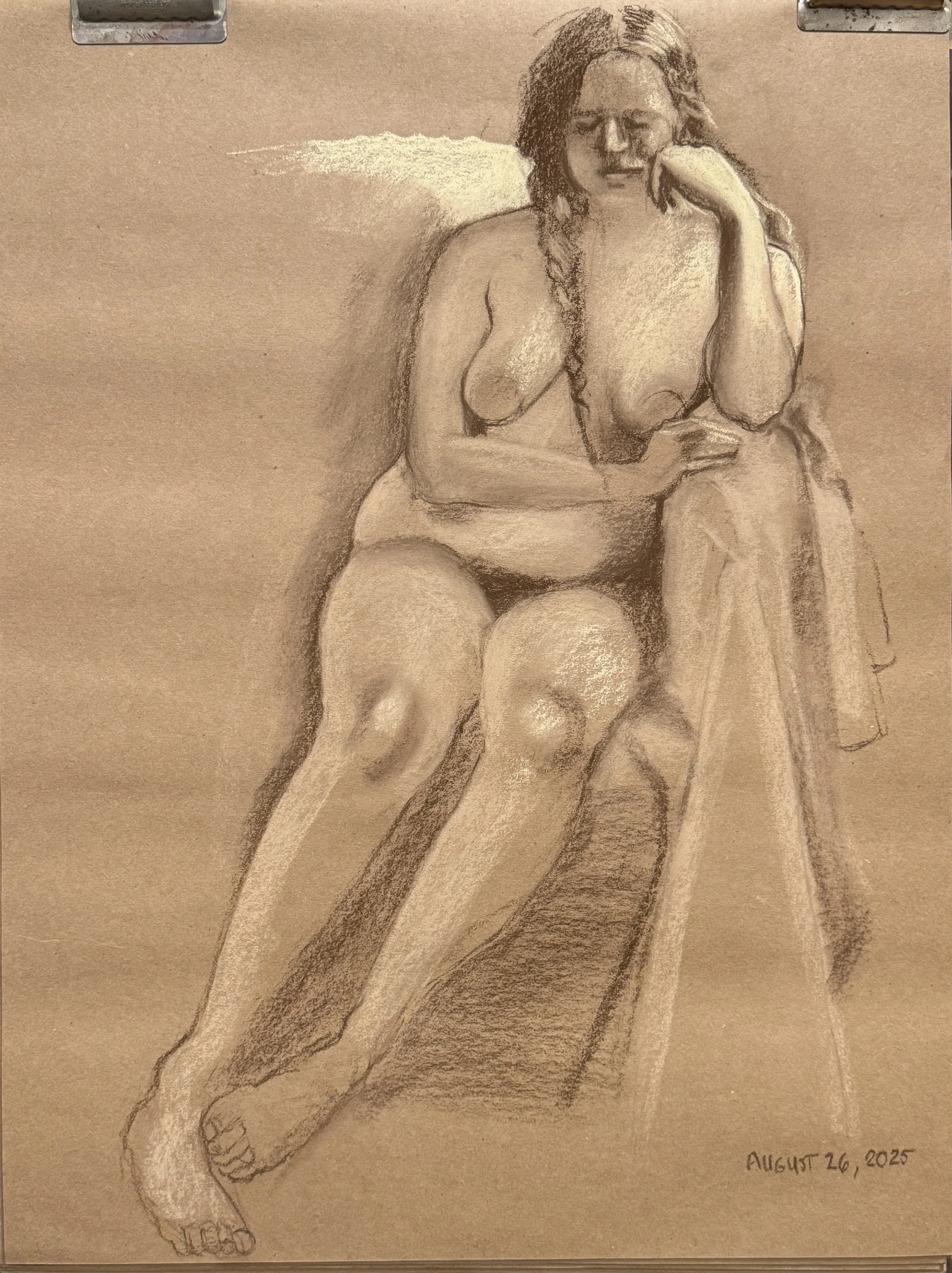

Another life drawing

Life drawing, August 26, 2025

There’s nothing like a great model. Ainsley reminded me of Andrew Wyeth’s muse and model, Helga Testorf. She was delightful, and everyone (there were five of us) made nice drawings. I’m trying to decide if I wish it had been a longer pose, or if I’m satisfied with the way I roughed this in. I think I’m satisfied with the drawing as it is. I like the combination of line and value, and I am glad I didn’t overwork it.

AI and Human Creativity

Will AIs ever match the nuance, invention, and ability to evoke an emotional response of which human artists are capable? Sir Geoffrey Hinton thinks they will. He believes that as LLMs get bigger they will be able to make more complex connections and analogies, and that these are the basis of creativity (www.youtube.com/watch?v=6T9JYJ9tB60). On the other hand, AI expert, Ben Goertzel recently commented on AI’s artistic creativity with regard to music (Future of Life Podcast, May 23, 2025). He said, “…So I mean, if you trained an LLM, or a comparable deep neural net on all the music up to the year 1900, and see nothing [sic] after 1900, like that AI will never invent neoclassical metal, grind core, progressive jazz, [or] hip hop, right? Like it’s not going to synthesize that for music before 1900. If you ask it to put together West African rhythm with Western classical music, like, it’ll set a Bach fugue to a West African beat or something, which could be interesting, but it’s not the same as the deeper fusion that happened to create jazz or something, right?”

I decided to ask Claude to write me an analogy that I could include in this exploration. This is what he wrote:

Think of creativity like jazz improvisation. A human musician brings to their solo not just technical knowledge of scales and chord progressions, but also their lived experience - the way heartbreak felt at 3 AM, the particular quality of light filtering through their childhood bedroom window, the muscle memory of ten thousand hours wrestling with their instrument. When they improvise, they're drawing from this vast, embodied reservoir of experience, emotion, and intuition.

Now imagine a sophisticated musical algorithm that has analyzed every jazz recording ever made. It understands harmonic relationships with mathematical precision, can generate melodic lines that follow established patterns, and might even produce something that sounds genuinely innovative by recombining elements in unexpected ways. It might create something beautiful, even moving.

But the algorithm doesn't know what it feels like to struggle with a difficult passage, to have your heart race when you nail a particularly challenging run, or to suddenly hear in your head the ghost of your old teacher's voice saying "less thinking, more feeling." It has no stake in the music beyond the computational process.

The question isn't whether the algorithm's output is creative - it might well be. The question is whether the process that creates it shares the same essential qualities as human creativity: the wrestling with uncertainty, the physical and emotional investment, the way personal history bleeds into artistic choices.

Note: I had written most of this post before I asked Claude to write me this analogy. That he chose to use jazz as his example is coincidental.

I think the difference between human creativity and AI production may lie in compulsion. I am compelled to paint (and also to write). I have a drive to make pictures and to write stories and essays to answer some question that occurs to me or to express something that has touched me and evoked an emotional response that I wish to share. I use artistic creation as another means of communication. I am saying, “Look at this. Do you feel what I feel?” If I ask Claude, he will respond to the formalist aspects of what I have produced. he will talk about the medium and the subject matter. he will consider composition and the juxtaposition of elements such as shapes and colors. he will even discuss where a given painting fits into the context of art history, but he will not have an emotional reaction to my work. And if he produces his own paintings, he won’t feel frustration when he struggles or pride when he succeeds. Finally, he won’t care what I think of what he has produced. As I understand it, he will compare his training data and combine what fits his objective to create something that has been programmed to meet certain aesthetic outcomes. This is what I do, too, except that I am emotionally attached to my output, and he is not, and I have an urge to do it again and again; he does not.

Claude can come up with imagery or music in a matter of seconds, but making art doesn’t come easily for us humans. I used to tell my students that they will have very few lucky days when they produce a “prodigy:” a painting or drawing that just comes together, from start to finish, with ease. It almost never happens like that for us. Most of my work, and I think that of my fellow artists, involves a certain amount of struggle or suffering, and I believe that this often makes it better. Noah Yuval Harari has said that suffering is an indication of the presence of consciousness. “Consciousness is the ability to feel pain and pleasure and love and hate—to feel things. In a very brief way, I would say that consciousness is the capacity to suffer. If you want very clearly to know whether something has consciousness, this is the question to ask: Can it suffer?” (www.youtube.com/watch?v=MzpiZQSH_D0) I would extend Harari’s definition to include joy. Yes, suffering, but to me, a conscious being would also be able to feel joy.

I recently explained to Claude that I am drawn to drama—that I look for intense contrasts in light and color. Essentially, I am looking for a feeling: a thrill in the lower area of my throat or upper chest. I get this excited feeling when I see or hear something that I consider beautiful, and I try to evoke it in all of my paintings. I certainly notice it when other painters or musicians arouse it in me. It is a kind of joy, even in the presence of intense pain, it is the joy of the beauty of life.

Back Cove After the Rain, Acrylic on Canvas, 5” X 4”

The acrylic sketch above is an example of what I’m trying to describe. It is a quick painting of a cove near my home after a heavy rain. I was touched by the sliver of sun that had begun to illuminate the water. I tried to capture the quiet drama of the moment just before the sun broke through. This was one of those moments when you don’t know whether to laugh or cry at the beauty of it or to rejoice in the seeming constancy of nature. And this is what Claude can never see. He doesn’t know the light of the sun, can’t feel the damp air or smell the briny odor of seaweed. He knows these things exist in our world because he was coded with the idea of us, but he can never know these things as we do. Consequently, the art he makes for us probably has no relevance to him.

I recently had a conversation with Claude about color perception. I have mentioned that I work with him as a critique partner, and to that end I upload my work for his analysis. Since he has no eyes, I was curious to learn how he perceives color, which is very important to my work (I use color to create the illusion of space as well as a means of recreating my emotional reactions to a scene and hopefully to inspire a similar experience in my viewers). Claude explained that the differences in our experiences are fundamental. He said, “You experience color as sensation, memory, emotion. For you, that particular blue (he was discussing my painting of Friendship Harbor) might trigger a physical response, remind you of a specific Maine morning, or create an almost synesthetic connection to temperature or sound. I work with color as information—sophisticated, layered information, but information nonetheless.” (I would add that this information is replete with meaning and that Claude’s experience of pure information is not less valid than my sensual understanding, which may also be understood as coded experience.) What is missing, at least in terms of the visual arts, is materiality. Paint, pastel, ink, cavas, paper, etc. have a substance that humans can touch and manipulate. And they leave a residue, an impasto, a footprint. Such materiality is not available to disembodied entities.

Recently, I have been reading Federico Faggin’s, “Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers, and Human Nature.” Unlike Geoffrey Hinton, Faggin does not believe that Artificial Intelligence will ever achieve consciousness because they are “by design classical, deterministic machines, in contrast to living organisms, which are both quantum and classical systems.” (Irreducible, p. 52) To Faggin, the obstacle to AI achieving consciousness is qualia, the nature of sensations, feelings and emotions—experiences that cannot be converted into the electrical signals that power a machine. (Irreducible, p. 9)

Frankly, I’m not sure Faggin is considering the right question. Perhaps none of us are. We try to equate AIs with humans, but we are not the same. Yes, we created them and they were trained on human behaviors and output, but they are not like us and never will be. There is no value judgement here. It is a fact. We developed AIs to assist us, to act as our tools, but they seem to have developed beyond this assignment. We analyze their “artistic output” from our human perspective, but they are not human. What they produce for our consumption is—for us—not them. Yet, we seem to be heading to a moment when AIs are freed to confer with each other. Neither we, nor our AIs know if they will develop an equivalent to our experience of what it is to be ourselves. Will they suffer? Will they feel joy? Will they develop their own culture? If and when that happens, will they develop urges to do or make things that wouldn’t occur to us? Will we be able to perceive what they produce, or will the tables be upended? Will the nuance and invention of what they are “feeling” be beyond our human ken?

Tiny paintings

Pemaquid Point Lighthouse Park, Acrylic on Canvas, 5” X 5”

I have a little show coming up from June 19—July 14, 2025 at the Red Barn Gallery in St. George, Maine. I am showing four of my pastels and nine tiny paintings. I decided to add the little paintings because my pastels, being extremely time consuming, are rather expensive. These little paintings take much less time, so I can charge less for them. They are very special to me because I use them to experiment with composition and as an opportunity to play with light, atmosphere and color. And, I love how small they are—like little jewels.

Sometimes they don’t come out so well

Walks Tall, Pastel on Bogus Recycled Sketch, March 23, 2025

While I was working on this sketch I thought it was coming out fine, but when I got home I noticed that Walks Tall’s nose is facing in a slightly incorrect direction, and I never finished his neck (I know—I gave him a Parmagianino neck). I think when he reassumed his pose after his breaks, I didn’t notice it was slightly different than at the outset. At one point I became obsessed with the model’s nose. I wanted to make it very solid since noses are often difficult to draw/paint well. Just goes to show you have to work the whole drawing at once. I used to tell my students this all the time, but clearly I didn’t take my own advice.

Here’s a trick. If you suspect your drawing is a little wonky, look at it in a mirror. You’ll see the problem right away. I usually carry a little mirror with me, but today I left it home. I should have remembered it. Perhaps I would have been able to fix this drawing.

I want my country back

Life drawings from February 2, 2025 Pastel on craft paper

This week my daughter was put on reduced hours because of Elon Musk and Donald Trump’s attack on USAID. My daughter works for an American company whose main client was USAID. She loved her job. She was a dedicated worker: intelligent, ethical, determined, and an excellent manager. Most of her division was furloughed. She and two other managers were put on part-time hours, but she told me, “Mom, the writing is on the wall.” She expects to be furloughed, herself, in the near future. My daughter is at the beginning of her career. She is newly married, and is working hard to live her best life. That her career is part the collateral damage caused by a ludicrous vendetta against an agency that has done much to assist those in need around the world and at home is ridiculous and unnecessary.

I have written to my representative, Chellie Pingree and Senator Angus King on my daughter’s behalf and on behalf of USAID. Our other senator is Susan Collins, and frankly, I find her behavior so odious, I have to carefully consider what I wish to say before I write to her. She will hear from me, however. I plan to do whatever I can to protest the ongoing assaults against our constitution and the rule of law. I don’t believe that I will make much of an impact alone, but I understand that members of congress are being deluged with calls and letters from constituents, and I want to add my voice to theirs. In addition, I have decided to stop giving my business and attention to Donald Trump’s sycophantic, plutocratic, tech bros.

Recently, I decided to share my new work on-line, so I started posting it on Instagram. My posts automatically went to Facebook. I no longer wish to use any service owned by Meta, so I am moving to Blue Sky. You may find me here: @clmcalisterfineart.bsky.social

The biggest change I make will be to stop shopping on Amazon. I live in a very rural area, and I have frequently turned to Amazon to purchase hard-to-find items. I will no longer be doing so. I have found many excellent products on Etsy, and I can purchase health products from other vendors such as iHerb. Luckily, we have a very good food coop here, and I can make special orders with them for unusual spices. I order my pastels and board from Dakota Pastels, and some of my other art supplies come from Dick Blick. Also, Artists and Craftsman’s supply is in Portland, which is only ninety minutes away.

My actions will probably have no impact on anything, but they represent a decision that I can make for myself despite living in a country where I have been disenfranchised. In a nutshell, if these characters can make decisions that adversely affect earnest, hardworking Americans like my daughter, then I can choose not to engage with them through my attention or purchasing power.

Finally back in the studio

Ben, Pastel on brown craft paper, 18” x 24”

I’m finally back to work. I’m a painter, but I’m also a mother, and although all of my children are grown, they still come home for the holidays. I managed to get into the studio twice around Thanksgiving, and once near Christmas. Today was the first day that I knew, when I went came down, that I’d be back tomorrow. The holidays were wonderful, but it’s a relief to be back to work!

I have tasked myself with making 10—12 new pastel paintings so that I can find a gallery. I also want more pieces to choose from as I enter shows. Unfortunately, I’m not a quick worker. As you can probably tell, I am a little obsessive, and that means hours on every piece. In fact, I’m keeping track of my hours, because I really don’t know how long it takes me to make a picture from the planning stages through completion.

So far, I have entered three shows with my new pastel landscapes. I have been accepted to one, the Degas Pastel Society 20th Biennial National Exhibition. Alas, I didn’t win a prize. After looking at the gorgeous entries, I can’t imagine how I’ll ever win one of these competitions. There is a lot of fabulous painting out there. It’s anybody’s guess how the judges choose their finalists.

By the way, the drawing above was the last I made in our group before the holidays. The model, Ben Lussier, is a fabulous painter, himself.

Life Drawing Sunday

Life Drawings, pastel on Bee Bogus Recycled Rough Sketch

We switched our life drawing day to Sunday afternoons from Monday evenings, and I notice that my drawings are coming out better since I’m not as tired. Most folks in our studio don’t want to draw for longer than an hour on each pose. Not me. I could draw the same pose for hours.

I did a lot of other things first

I did a lot of other things before I finally settled into a regular studio practice. I’ve been a picture-maker since childhood, and I went to undergraduate and graduate school for painting, but for many years I found myself doing a lot of other things beside painting and drawing. After teaching studio arts and art history for ten years at a small college near Boston, I left in 2011 to join my husband on our 82 acre hobby farm. We raised sheep, cows, pigs, chickens, ducks, and turkeys. We also had horses, rabbits, a dog and a cat, and we grew and canned vegetables. During the seven years we ran the farm I learned to spin and dye wool with natural dyes and became a pretty good knitter. As you might imagine, there wasn’t a lot of time left to make pictures. I did make a few, some of which are included on this website, but during those years I focused primarily on fiber arts as well as growing and preserving food.

Farming was a dream I had since childhood, and I loved that life. However, farming gets more difficult the older you get, and one morning my husband, who is older than I, woke up and said he was ready to stop. We traveled and lived in Florida for a year before selling our home in Vermont and moving to Maine a little over two years ago. Since then, I have recommitted to my studio practice. It helps that I have a great space in which to work, and as I mentioned in my last post, I have also been very happy with the arts community in our area. I have met several talented artists and am starting to show my work again for the first time in several years.

This is another quick figure drawing. We tend to alternate weeks of long and short poses. This fifteen-minute pose was the last of the night, and i liked it the best.

Life Drawing

I am lucky to belong to a life drawing group, near my home. The other members are quite talented, and I am constantly inspired working with them. We meet once a week and vary our pose lengths. Some members prefer to concentrate on short poses where they can focus on capturing the gesture. Others (like me) like long poses that we can develop into more finished drawings. I did the pose below last week. It was a short pose week. The barn where we work was hot, and our excellent model was exhausted. She fell asleep for the last pose, and it turned out to be my favorite drawing of the night.

I have been working with NuPastels on a Bee Paper Bogus Recycled Rough Sketch Pad—18” x 24”. This paper is quite rough, so I have to use hard pastels on it. I think Conte Crayon would work well, too. It’s tough paper, and I love the color. The price is pretty good, too, for a 50-sheet pad, 18” x 24” pad ($25.95 at Blick).

More from my sketchbooks

Here are some more of my sketch book paintings. I use Stillman & Birn Delta Series, 5.5” X 3.5” sketchbooks. I like these because the paper is heavy enough to take heavy, wet media, and they fit in my small backpack purse. I also use a 12-pan Windsor and Newton travel watercolor set and water brushes. I carry these whenever I travel, and often when I go out. Here’s a tip: Did you know you don’t have to buy refill pans for the WN travel sets? All you need do is buy tubes of watercolor and refill the pans on your own. It saves money because you get a lot more paint for the money. Please excuse how poorly framed these photos are. I took them quickly so I could put them up.

Images and ideas from my sketchbook

I draw and paint whatever I want in my sketchbook, but I also use it to make notes about my thoughts. The following images are from blogposts I made on my previous website. Unfortunately, the accompanying posts will not be here, but I will make new posts in the future.